Harris Dickinson's fierce directorial debut is a poignant tale of a down-on-his-luck drifter, featuring a star-making performance from Frank Dillane.

Harris Dickinson's fierce directorial debut is a poignant tale of a down-on-his-luck drifter, featuring a star-making performance from Frank Dillane.

It’s easy to feel invisible in a city of 8.8 million people – even more so if you’re one of London’s estimated 12,000 rough sleepers. Mike (Frank Dillane) seems to take it mostly in his stride; he’s figured out the best spot to hide his meagre possessions (behind two commercial bins) and only seems mildly irritated when he’s woken from his spot on the pavement by an over-zealous street preacher with a PA system. But to the legions of fast-moving commuters in East London, he might as well be a ghost. Even when Mike does receive a small gesture of kindness from a stranger, desperate and distrusting as he is, his instinct is to do something deeply cruel in response. So sets in motion the plot of Harris Dickinson’s Urchin, a contemporary tragedy that draws on the likes of Mike Leigh’s Naked and Agnés Varda’s Vagabond in its piercing observation of modern life on the fringes.

Dillane (also brilliantly nasty later this year in Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Harvest)is a remarkable discovery, totally at the heart of Dickinson’s script and lens. His puppy dog eyes and shaggy haircut project a certain softness; he’s boyish and charming in fits and bursts, clearly street smart and charismatic, but knocked down enough times that getting back up is that little bit harder each time. Mike’s obvious vulnerability in juxtaposition with his occasional violent outbursts evokes De Niro’s Travis Bickle with a dash of Kes, while Dickinson’s decision to give us only a few details about the circumstances that have led to Mike’s perilous existence encourages empathy without exception. There’s no real need to know how or why Mike got here; the details are largely immaterial to his situation. Yet Mike’s reluctance to confront his past (and his personal shortcomings) hardly help; time and time again, it’s Mike who trips himself up just as the ground ahead seems sure. His tendency to glaze over his own sadness or frustration with a placid grin is only effective for so long.

If a story about an unhoused young man trying to pick his way through the hellscape of the modern capital doesn’t sound very sunny, it’s true that there’s something deeply melancholy about the existence Mike is barely eking out, and his isolation is palpable and raw. But Dickinson – a talented comedic force on-screen in his own right – finds lightness there too, and a combination of sharp dialogue and excellent delivery from Dillane et al (including Dickinson himself as Mike’s sometime mate Nathan) keep the audience on their toes. Urchin is never relentlessly grim, even if it finds enough bleak moments that Leigh comparisons are well-earned. Nor is this a posturing ‘issue’ movie, peering down at London’s rough sleepers with a patronising pat on the shoulder. There’s a clear understanding of the forces that lead people to addiction and homelessness, and how without proper infrastructure and support, willpower can’t sustain recovery alone. Dickinson affords more tenderness to his protagonist than London is willing to, but it’s also clear Mike’s no angel (nor should he have to be to earn our empathy). Instead he’s familiar in his specificity, emblematic of thousands slipping through the cracks as those in power show more and more contempt for the most vulnerable.

As for Harris Dickinson, it’s only mildly galling to see how bloody good he is at everything he turns his mind to, here on writing, directing, producing (through his production company Devisio with Archie Pearch) and supporting actor duties, yet deftly refuting any vanity project allegations by virtue of creating a phenomenally impressive debut feature.

To keep celebrating the craft of film, we have to rely on the support of our members. Join Club LWLies today and receive access to a host of benefits.

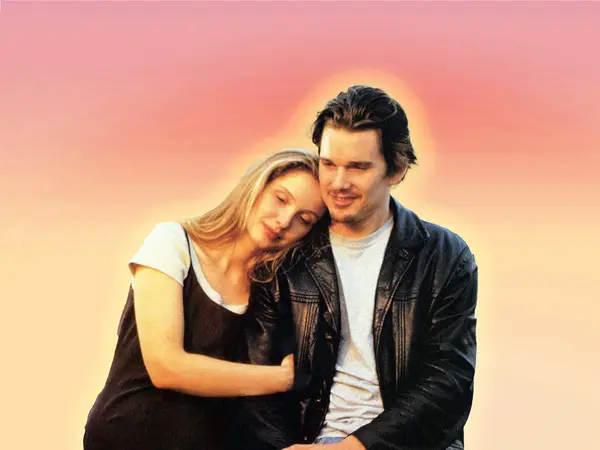

Before Sunrise and the ultimate intimacy

Before Sunrise and the ultimate intimacy

How To Train Your Dragon | Lollipop | Ladybird Ladybird (1994)

How To Train Your Dragon | Lollipop | Ladybird Ladybird (1994)

Protein review – nasty, funny, soulful

Protein review – nasty, funny, soulful

Daisy-May Hudson: ‘I want to make films that crack people’s hearts open’

Daisy-May Hudson: ‘I want to make films that crack people’s hearts open’

The Dreamworld Aesthetic of 8½

The Dreamworld Aesthetic of 8½

How To Train Your Dragon review – never quite catches the updraft needed to soar to uncharted heights

How To Train Your Dragon review – never quite catches the updraft needed to soar to uncharted heights

This Must Be the Place: A Queer East Correspondence

This Must Be the Place: A Queer East Correspondence

Lollipop review – a gut-punching debut

Lollipop review – a gut-punching debut

Tornado review – tries a bit too hard to be different

Tornado review – tries a bit too hard to be different

Introducing… La Dolce Vita: A Celebration of Italian Screen Style

Introducing… La Dolce Vita: A Celebration of Italian Screen Style

Dangerous Animals | Ballerina | Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979)

Dangerous Animals | Ballerina | Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979)

The Encampments review – inspiring portrait of collective action

The Encampments review – inspiring portrait of collective action

Falling Into Place review – Sally Rooney-core for the big screen

Falling Into Place review – Sally Rooney-core for the big screen

Dangerous Animals review – why sharks? They’re cinematic!

Dangerous Animals review – why sharks? They’re cinematic!

Cannes Film Festival Debrief 2025

Cannes Film Festival Debrief 2025

Bogancloch review – film and landscape are as one

Bogancloch review – film and landscape are as one

The Ritual review – fails to scare, entertain or convert

The Ritual review – fails to scare, entertain or convert

Along Came Love review – an intimately epic love story

Along Came Love review – an intimately epic love story

The Ballad Of Wallis Island review – relishes in daft physical comedy

The Ballad Of Wallis Island review – relishes in daft physical comedy

Resurrection – first-look review

Resurrection – first-look review